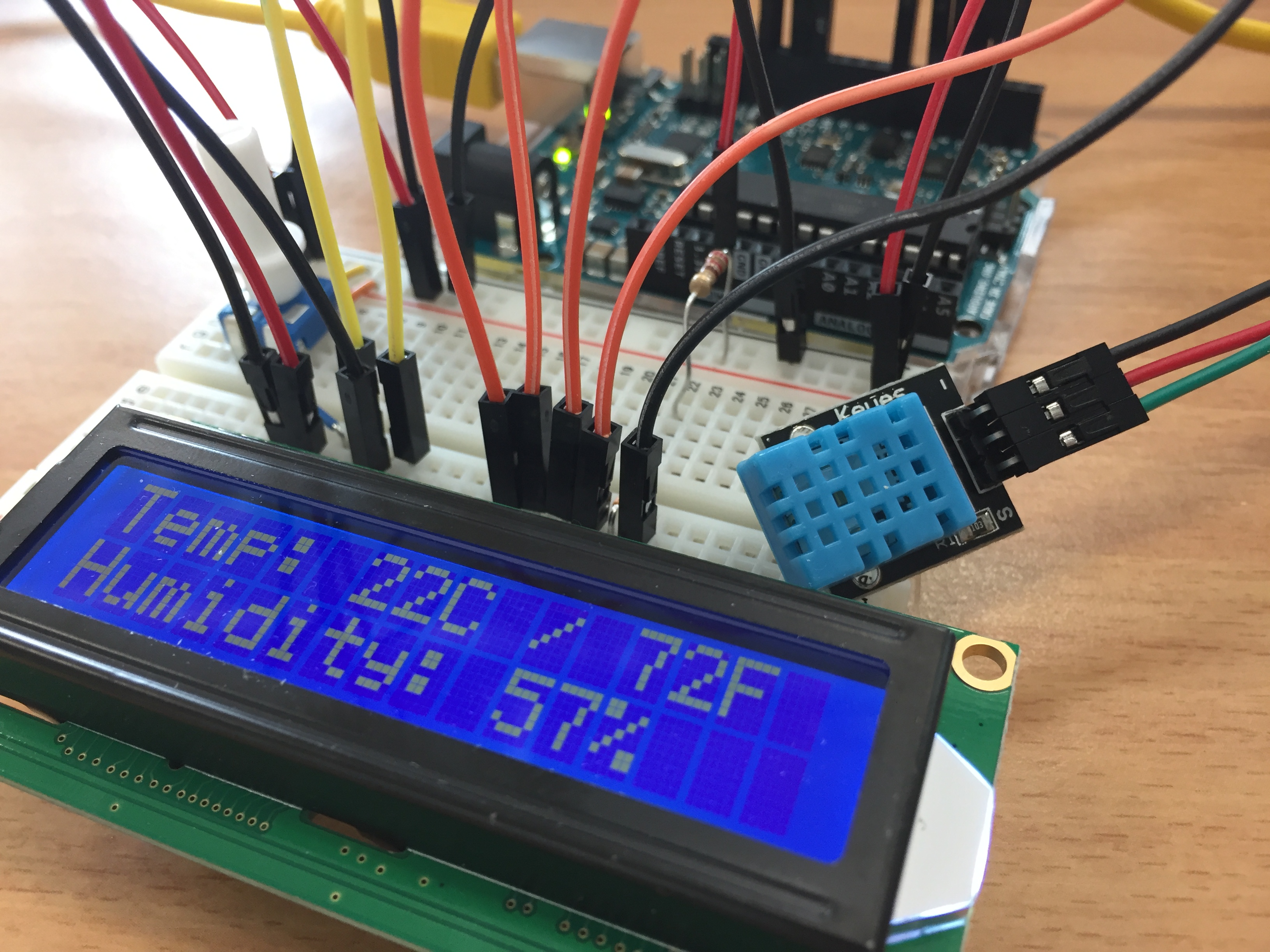

Display temperature and humidity data on an LCD

My friend Afra invited me to participate in a conference in Sweden involving sustainable urban greenhouse solutions. Så Ett Frö (Plant a Seed) is a collaboration with HSB Living Lab, a 10-year-long experiment which uses technology to help build more sustainable housing building.

My job was to automate a small greenhouse using my budding Arduino skills. The main objective of Så Ett Frö is education amongst grades 7-9. So for now we haven't spent time calculating economic value or carbon footprint. Future iterations will hopefully allow us to tackle these engineering issues which will make the greenhouse more sustainable.

Temperature and humidity readings

I've already used a soil moisture sensor so my first assignment was to integrate a temperature/humidity sensor into the greenhouse. We used the well-known DHT11 because it was available everywhere and there are two good libraries for reading data from it.

The setup is as simple as can be. VCC, GND, and a SIG are all the connections you need. In order to report both temperature and humidity, the DHT11 sensor outputs a stream of 40 bits so there are libraries to help read the raw data off whatever pin you connect. That means you can plug SIG into any pin, analog or digital. We waited until setting the LCD up to choose a pin.

To read data, we opted for the SimpleDHT because we did want to keep it simple. There's another more standard library but they both work the same and I was able to peruse the entire source code of the SimpleDHT lib and understand what it was doing a bit more thoroughly. You can install it via the Arduino IDE by navigating through the menu as follows:

Sketch » Include Library » Manage Libraries...

Once you're at the library manager search for SimpleDHT. Install the latest version so it's available to the IDE as an include (more on that later).

Connecting the LCD

We had an LCD from the Arduino Starterkit, a backlit display with two 16-character rows. I'll skip the connections because we followed the official LCD connection instructions without making any modifications. If you follow that tutorial you should be good. Our code below uses the pins in that tutorial, in case you're wondering about the numbers supplied as parameters to the lcd() initialization below.

You'll notice the official tutorial includes a potentiometer (a knob). It controls the contrast of the display. If it's unreadable give the knob a twist and find the right setting so the characters are easy to read. While wiring our display, we tried to make it "easier" by omitting this component... it made it more difficult in the end. Be sure to include it!

After connecting everything for the LCD, we chose digital 6 for our DHT11 signal since it was still available, and lining up all the pins next to each other makes adding additional components easier.

Formatting data for display

We did a quick Serial Plotter test to ensure everything was working correctly, and then wrote the following code to send the data to the LCD.

#include

#include

// Initialize humidity sensor.

const int pinDHT11 = 6;

SimpleDHT11 dht11;

// Initialize LCD

LiquidCrystal lcd(12, 11, 5, 4, 3, 2);

// Setup LCD and display startup message

void setup() {

// Display is two 16-char rows

lcd.begin(16, 2);

// Print a startup message

lcd.print("Startup OK!");

delay(1000);

// Clear display so we can show data

lcd.clear();

}

// Display temp/humidity data until power-down

void loop() {

// Create variables for DHT sensor output.

byte temperature = 0;

byte humidity = 0;

// Read sensor data and store results

// in temperature/humidity variables

dht11.read(pinDHT11, &temperature, &humidity, NULL);

// Print first line to LCD

lcd.setCursor(0,0);

lcd.print("Temp: ");

lcd.print(round(temperature));

lcd.print("C / ");

lcd.print(round(temperature * 1.8 + 32));

lcd.print("F "); // two extra spaces in case temps drop to single digits

// Print second line to LCD

lcd.setCursor(0,1);

lcd.print("Humidity: ");

lcd.print(humidity);

lcd.print("% "); // extra space in case humidity drops to single digit

// Delay 1 second because DHT11 sampling rate is 1HZ.

delay(1000);

}

The code is pretty straightforward. I'll highlight a couple points that were not obvious to the newer coders involved with the project.

The #include statements at the beginning reference libraries available to your Arduino IDE. Remember when we installed SimpleDHT before using the IDE? The include statement won't work unless it was installed beforehand. The LiquidCrystal library comes pre-packaged with the Arduino IDE, so that include statement doesn't require a download beforehand.

The dht11.read() function doesn't return output. Instead, the & symbol in front of &temperature and &humidity means that the variables are passed by reference. That is, instead of returning new values, the read() function alters the variables we supplied. This can be destructive, but since each new loop resets them to zero, this simple code doesn't have the possibility of data loss.

The LCD's setCursor command is zero-based, meaning the 16th column is 15 and the 2nd row is 1. So the top-left would be setCursor(0,0) and bottom right would be setCursor(15,1).

We attempted to use the degrees symbol for the temperature, but the display output other characters instead. The symbol does happen to be in the display's character set, but it's good to be aware that the display doesn't contain all the modern conveniences that make text so easy to render on a word processor or web page.

We noticed when the readings dropped to single digits that the last character in the display seemed to be printed twice. But they aren't, the real issue is that when the shorter string is printed, it doesn't automatically overwrite the previous string. Adding a lcd.clear() caused a small but noticeable blink in the display, so I opted to pad the output with spaces in the case that the readings change from double to single digit. This solves the visual glitch while maintaining persistence for the static labels on the display.

Reading results

After everything was connected and running properly, this is what we saw on our display. We tested that it worked by cupping the sensor in our hands and blowing into them. Human breath is warm and humid so the numbers should both go up after a few breaths of air.

More advanced uses of the LCD

Each character of the LCD is actually a 5x8 matrix of booleans. That means you have 40 bits that you can manually draw within each character if you're so inclined. 40 bits x 16 x 2 = 1280 bits total. If you are willing to sit and hand-code a drawing, you can make a fairly high-resolution picture. You could also make manual drawings of any character you want if it's not included in the default character set, then just reference them using variables.

The display has a decent refresh rate, so you can achieve a few levels of brightness by redrawing a few times per second. But like all LCDs it has some "memory" between each pass so don't expect the same amount of precision that you can achieve with PWM on a LED.

Webmentions

Have you linked to this page from your site? Submit your URL and it will appear below. Learn more.

Mentioned by

Building an automated greenhouse with Arduino

My friend Afra invited me to participate in a conference in Sweden involving sustainable urban greenhouse solutions. Så Ett Frö (Plant a Seed) is a collaboration with HSB Living Lab, a 10-year-long experiment which uses technology to help build more sustainable housing building.

My job was to automate a small greenhouse using my budding Arduino skills. The main objective of Så Ett Frö is education amongst grades 7-9. So for now we haven't spent time calculating economic value or carbon footprint. Future iterations will hopefully allow us to tackle these engineering issues which will make the greenhouse more sustainable.

Building the frame

We know our strengths and working with wood wasn't one of them. Luckily Afra has a friend who is quite talented working with wood, so in an afternoon while we debugged the LCD, he was building the frame of our greenhouse. He used scrap wood from HSB Living Lab, and some used plexiglass that Afra obtained from the city that would have been thrown away.

In the end it was approximately 80x60x80 centimeters, roughly the shape of a classic PC tower. One of the small sides has a hinged door and all other entry points were created by drilling holes in either the plastic or notches in the wood.

Arduino components

We used the following sensors to collect data from the greenhouse:

We planned to use the following components to control the environment in the greenhouse:

- Arduino Uno R3

- Peristaltic water pump

- LED lamps

- Ventilation fan

- Photosensor (future)

- Real-time clock module (future)

- Solar panels (future)

- LCD for real-time data reporting

Arduino is the center of the automation system. It receives all the sensor data and responds by controlling most of the components.

The water pump provides plants with water. The watering is triggered by the soil moisture sensor, which can detect when the soil has become too dry. The pump can be quite small, and only has to run for very short periods of time to provide water to the plants. Unfortunately even a small pump requires an external power supply, because the Arduino can't handle the load of the motor when converted from 5V to 12V.

The LED lamps provide a supplement to sunlight energy. Of course, if there's sunlight available then it's preferential, but LED lamps can help out when the sun isn't shining as many hours during winter in places up north like Sweden. Ideally, we would use photosensors to detect light conditions instead of relying on timed schedules, but in cases where we only detect a few hours of light per day, the real-time clock can help guide the Arduino to turn LED lamps on for a few extra hours to hit a target light cycle.

Ventilation fans help regulate air temperature and humidity. Plants need air with CO2 to grow properly, and their "waste" is good for humans to breathe. So it's nice to stir up the air every once in a while. This is something that could possibly be handled by enclosure design rather than a fan, reducing the energy footprint. But for our prototype, we included the fan since it was a simple solution.

Real-time clock module helps keep regular schedules. Arduinos cannot reliably keep time, so a small module with its own coin battery helps provide some continuity in cases where the Arduino momentarily loses power or receives code updates necessitating a reboot. We didn't include the clock in our prototype this time, but it's good to keep in mind for the future.

Solar panels would ideally power the entire system. Ensuring that the greenhouse is not using grid energy is one of the most important goals of creating a sustainable solution. If the system requires more energy than a reasonably sized solar panel the responsible solution is to reduce our energy consumption, rather than increase panel size. A battery would be required as well, but we haven't made any progress on integrating the panel yet, so this is a problem we'll tackle in the future.

An LCD allows someone to check conditions of the greenhouse. While technically optional, it allows a novice grower to check on conditions and determine if changes need to be made to the system. It was also an appealing interactive component to our prototype since it was on display at a public event.

Building manual

Now in its second year, Så Ett Frö is accumulating knowledge by requiring that a manual be written once students are done building. The sharing of knowledge is the actual seed being planted!

Here's the manual from the first year (the website has been taken down), which includes detailed parts lists and instructions for how to build the entire structure.